Almost half of all New Zealanders drive less than 5km to work each day. This relatively small commute is possibly one of the most costly and unsustainable choices we make on a daily basis.

So, why do 90% of us choose our car as the primary means of transport?

To understand why, we need to confront the fact that humans are simply creatures of habit, and our car culture does everything to reinforce this habit.

Every point along our journey, from the moment we grab our car keys in the morning, to taking the ticket from the carpark vending machine, has been carefully optimised to make our commuting experience more comfortable, convenient and efficient.

Making things even tougher, our car habit is socially normalised, as smoking was for most of last century and eating meat has been up until recently.

We’re all doing it, so it must be alright, right?

Unfortunately not.

Studies in the U.S. have shown a 99% correlation between car use and obesity. One in three New Zealand adults are overweight, one of the highest rates in the developed world. Other New Zealand studies have calculated the cost of inactive people to our health system as high as $6.3 billion per year, with the major health issues being cardiovascular disease and cancer.

At least 30 minutes of moderate exercise is needed everyday to remain healthy. The equivalent of a 5km return trip by bike, or walk when catching a bus or train. Our daily car commute occupies the space that’s most convenient to exercise. This relatively small window of time is costing our health and economy big time.

The impact shoots well beyond personal health. As a society, we foot ever increasing road infrastructure costs to connect our car optimised suburbs, suffer lost productivity due to increasing congestion, and as a result continue to pump tonnes of carbon into the environment.

As tax-payers, we are essentially supporting our car culture to the sum of $20 billion dollars per year. Another way to look at it, is that we’re subsidising negative social, environmental and economic outcomes at a rate of $6500 per car commuter, every year.

The scale of this subsidy is difficult to comprehend, especially when you consider that these externalities are equivalent to, and on top of the $6500 average cost we personally shell out every year to keep our cars on the road.

It’s fair to say that our $40 billion car culture has reached population addiction status.

Addiction may seem like the wrong word to use however when its simple definition is applied: continued use despite adverse consequences - it makes sense. Like an addiction, our car culture is so compelling, so embedded and so convenient, we need far more persuasive means to enable mode shift.

The Personal & The Social

To affect a mode shift, we need to look at the reasons behind our addiction. To frame our enquiry, there are a few things we need to agree on:

Personal: Our day-to-day behaviour is largely habitual.

Personal: The anatomy of a habit is:

Trigger: Something happens and we register it as a positive or negative feeling.

Behaviour: We do something in response to the trigger. We move toward things that make us feel good and away from things that make us feel bad. We do this because it is our hard-wired survival response.

Reward: Our brains reward us if we’ve taken an action that aligns with our hard-wired response. The reward is designed to reinforce the trigger-response relationship.

Personal: Overtime, as habits are repeated and reinforced, they get stronger.

Social: Our habits are influenced significantly by what the community deems normal and abnormal behaviour.

To shift behaviour, we need unpack the personal and social levers and work out ways to push and pull them.

The Psychology of Habits

Habits are a normal part of our human psychology.

Without habits, we would not survive. These deeply embedded habits mean we will often continue doing something even if we know it’s having a negative impact. So much of what we do, we do it without much thought or self reflection, especially things that are part of our daily routines, like our food choices, the amount of social media we engage with and how we choose to commute.

Cars have become the perfectly rewarding habit in our increasingly busy, stressful and complex lives.

Similar to mobile phones, cars are exceptionally desirable objects, offering multiple layers of rewards to us consumers, including status, convenience, comfort and utility. Cars and the entire ecosystem that’s been built around them has been refined over decades to offer you the most rewarding experience.

Consider this common habitual experience.

Trigger: When we feel stressed and anxious in the morning because we’ve got emails piling up, sales calls to make, bills to pay, kids to get to school and a chaotic household to escape;

Automated Behaviour: We reach for our keys, jump in the car and drive to work.

Reward: Our brains are rewarded because we want the fastest and most hassle free way to get on top of (or escape) everything that’s creating stress and anxiety.

What makes our car culture so complex, is that the rewards are different for every one of us. For example, your reward might be the flat white or breakfast you enjoy on your drive to work. Or perhaps you enjoy the predictability and sense of being in control, or the quiet solitude of the experience. Or you just love the association with the car you’ve invested in – it’s become part of your identity.

We butt up against these triggers and rewards when confronted with change.

Change is uncomfortable, unpredictable and often threatens our identity. This is why mode shift is one of New Zealand’s most challenging societal transformations.

Breaking The Habit

To clarify, it is the behaviour of driving a car to work that we want to change. To do this, we have to enquire whether the rewards we get from driving are real, or really as good as they seem at first blush?

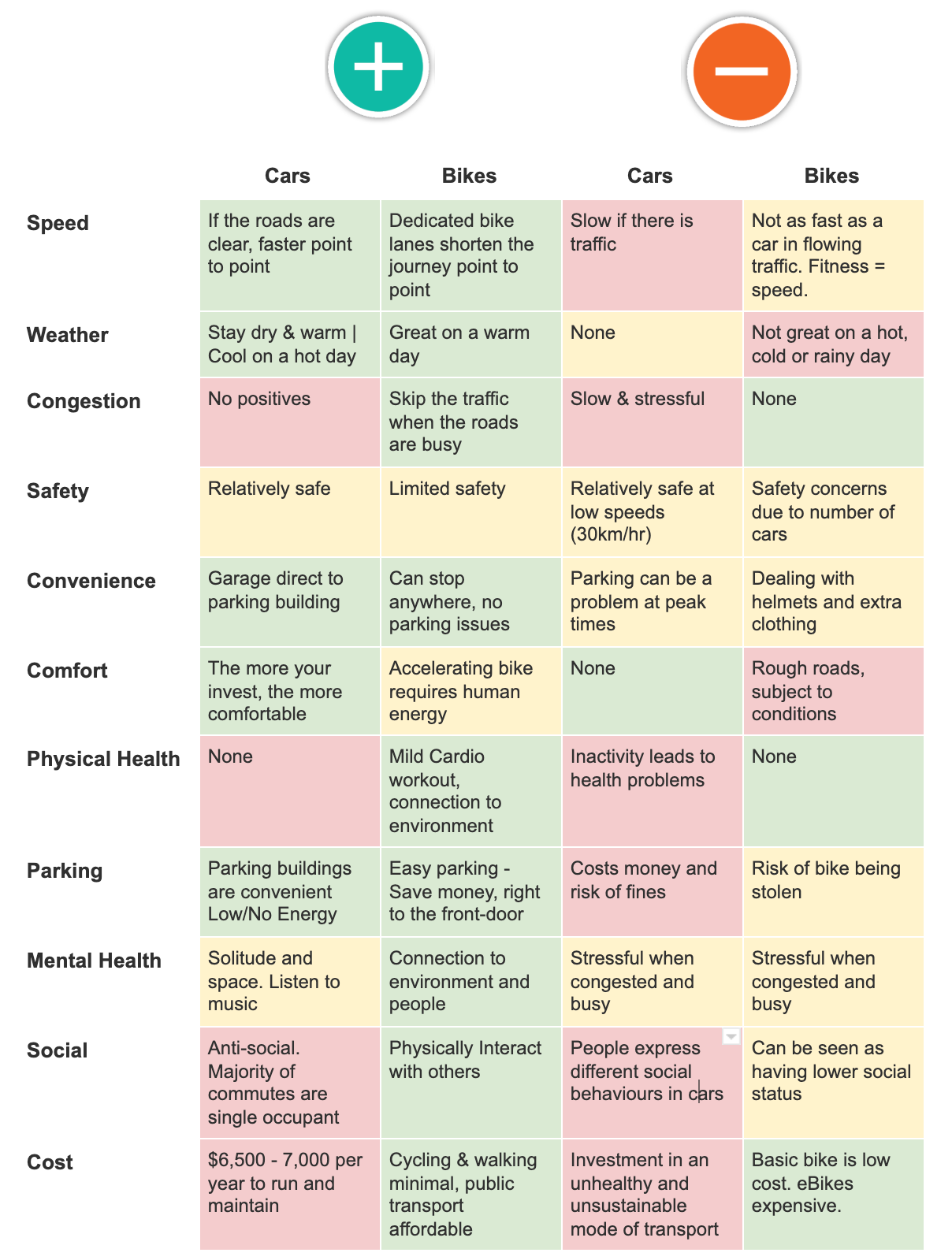

If we were to do a side-by-side comparison of the good and bad of driving to work vs active transport, how do the scales balance?

When examining the list above, and you bring awareness to your own experience, are you really getting the reward you thought you were from driving? Comparatively, how does biking or public transport look? What would it take to tip the scales in favour of active transport?

Willpower doesn’t change habits but bigger better offers do.

One of the biggest barriers we know to habit change is the “all or nothing” notion. Think about New Year resolutions. They don’t last. They don’t last because most of the time we frame a behaviour change in black and white terms. It’s often this framing that stops us trying in the first place; we know habit change is hard and we’ll likely fail so we never give it a shot. If you never give it a shot, you’ll never have a chance to explore something different.

The goal with the habit change journey is to have someone do something new, associate positive feelings with it and reinforce the new link between behaviour and the positive feeling.

Lowering The Barrier and Offering Rewards

Humans like to succeed; we hate failure. By creating a “game” that we are able to win, we are more likely to give something a try. So how do we remove barriers and create a “game” around cycling that means people can “win”?

Let’s take one very real barrier to active transport - the weather. Given weather is one of the biggest deterrents to cycling, why not create an initiative for people who live within 5km of work to publicly pledge to ride their bikes on sunny days only.

Call the campaign “The Sunny Day Riders Club”. The desire here is to have more people experience what it is like to ride a bike to work and be able to compare for themselves cycling vs driving. One day a week is a great start. One day can lead to two and so on but it starts with that one day a week being the most positive experience someone can have.

Prompting people to record how they how they feel before their ride to work, how they feel afterwards and importantly how they feel at the end of the day, would provide a qualitative way of having people become curious about the real rewards of biking vs driving. This kind of qualitative ‘feelings’ based feedback is what we capture at Sensibel.

Once people become aware of and are able to make a conscious choice about whether they get a Bigger Better Reward from a cycle to work vs. driving, a mode shift will occur.

For some people, simply making a public pledge to “play a game they can win” is all they might need to start biking to work on sunny days, but for others, an incentive might be necessary to get them to start & reinforce their commitment to “The Sunny Day Riders Club”.

Incentives

In a recent study conducted by Sensibel, it was determined that a monthly reward of a perceived value between $30-40 was enough to increase cycling retention. When calculated over a year, this is less than 5% of what the Government and ourselves personally invest into our car habit. This engagement finding may seem slightly trivial in the wider context of mode shift, but it does beg the question of why we don’t tangibly reward positive behaviour, rather than continue to collectively fund and reinforce negative behaviour?

What if joining “The Sunny Day Riders Club” and recording your bike each day earned you credits to directly pay-off an eBike? Or the credits gained from cycling topped up your family pass to the swimming pool or covered subscriptions to Netflix. What if you could also access discounts to health insurance or the gym? Or your ride simply got you a free cake or coffee from a local cafe?

Explicit incentives like those just mentioned play a massive role in sticking to a habit change journey. Old habits kick-in so easily in the beginning, especially deeply ingrained ones, and it’s easy to lose sight of the Bigger Better Rewards you’re discovering. An incentive can be enough to snap you out of your old habit loop, become aware again of the choice that really gets you the Bigger Better Reward & ultimately to have you keep your commitment to mode shift.

Rewards and incentives are common motivators used in retail to change purchasing habits and persuade people to try new things. The entire rewards marketing industry has been built on its success to create loyalty and retain customers. We see so much of it now that rewards of some form or another are almost expected.

When it comes to public transport or active transport, there are very few, if any, extrinsic rewards enticing us to step outside our normal behaviour.

The engagement dynamics that drive our social media and gaming industries are renowned for their ability to retain active users. Using points, rewards, notifications, social connectivity and smart algorithms that display content they know you’re interested in, these platforms (for mostly all the wrong reasons) keep us hooked, often for hours every day.

Digital rewards or virtual currencies have been proven to work and are at our disposal to actively enable positive behaviour change, yet they don’t currently factor into any known trip planning or mode shift initiatives.

Speeding Up The Process with Punitive Measures

It is often commented that doubling the price of petrol or increasing road user taxes would dramatically speed up the habit change and mode shift journey, because people (especially those on a low income) wouldn’t have a choice. However, the compounding impact of a punitive approach would be enormous. Freight and travel costs factor into the price of almost everything we buy. The cost of food would increase relative to the cost of freight. The outcome would be expanding our currently huge inequity gap and not encouraging positive behaviour change. At a societal level, cycling, walking or public transport could become even more tainted with social stigma than we currently experience.

What may have worked for smoking, is not the silver bullet answer to mode shift.

Breaking New Zealand’s Car Culture

Better and safer cycleways or more buses cannot compete with the level of service the car industry has directly and indirectly created in New Zealand. Most New Zealand cities are purpose built for our car culture. At the most extreme case, some of us would rather spend more than $10 billion to upgrade the congested Auckland Harbour Bridge, than to invest in reducing traffic through mode shift.

To break New Zealand’s car culture requires a shift in thinking from continual investment in hard infrastructure to smart investment in soft infrastructure. By soft infrastructure, we mean people. Switching to walking, cycling or public transport is not a simple proposition for most people, but with careful and direct encouragement, appropriate reward and time, social norms can be shifted.

Up until now, civil engineers have been retained to create mechanical cities based on traffic flows, it’s now time for the engagement architects to enable citizens to make their cities healthy and liveable and start changing our cultural narrative on mobility.